Is Europe Dying?

Europe may be stagnant but the world needs its unique monopolies

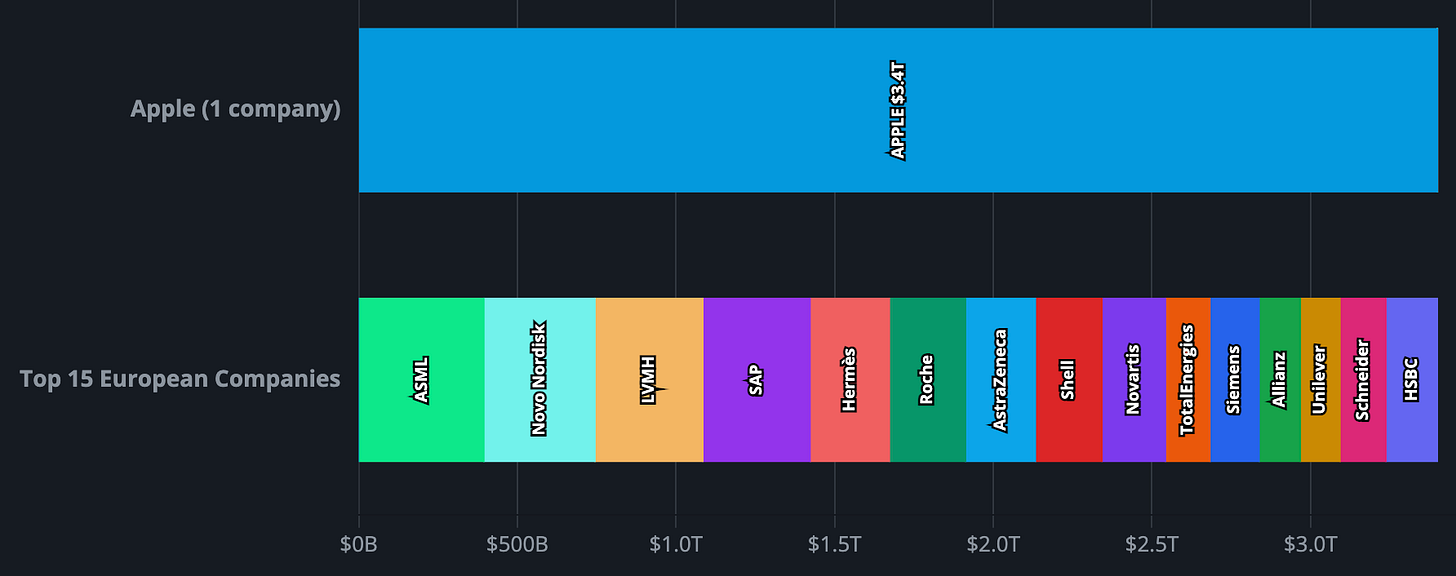

To equal the market capitalization of Apple today, you would have to take the top 15 largest companies in Europe and glue them together.

Combine ASML, Novo Nordisk, LVMH, SAP, Hermes, and ten others and you’d match the value of the iPhone maker.

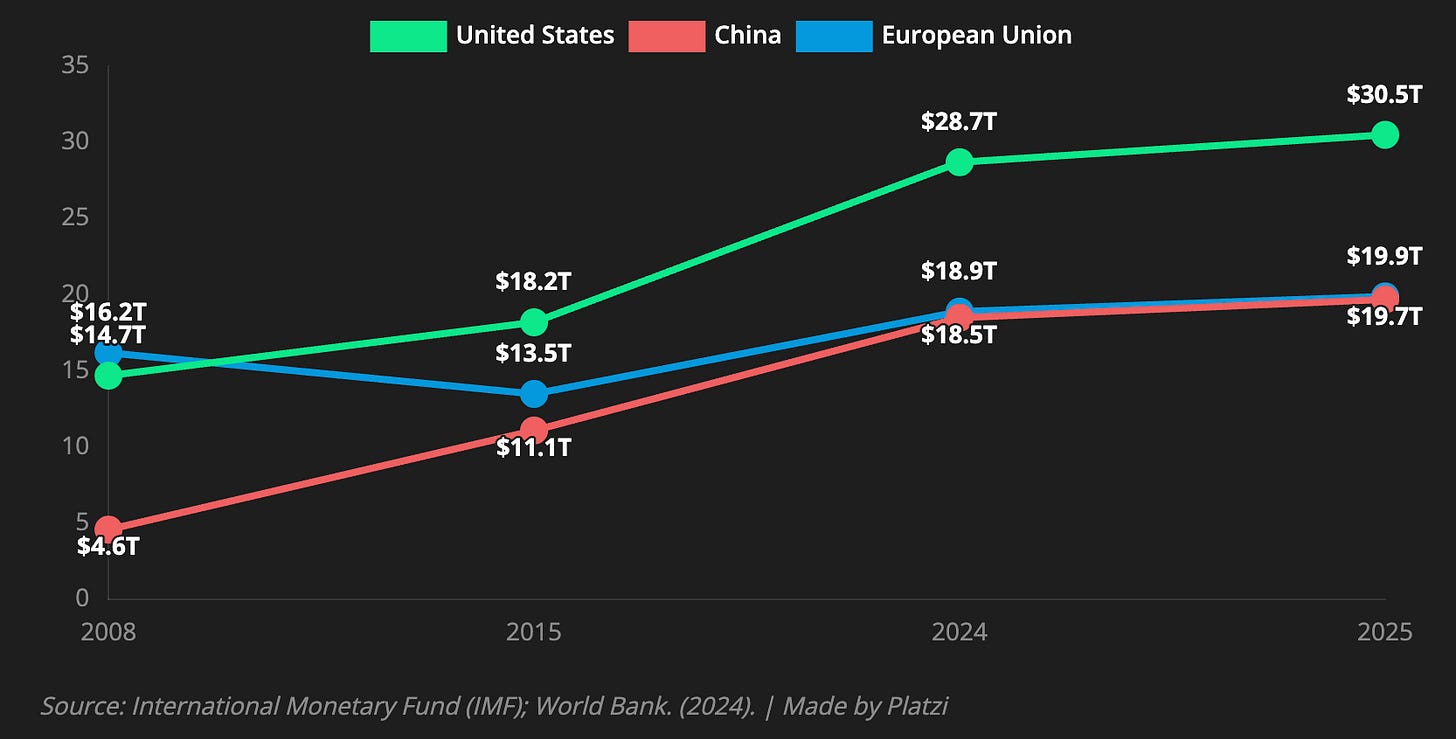

In 2008, right before the financial crisis, the European Union’s economy was 10% larger than the United States. Today, the US economy is significantly larger, and China has just overtaken the EU for the first time.

Europe is stagnant, aging, and regulated to the brink of insanity. But it also holds a chokehold on the specific technologies that keep the modern world running.

Here is the reality of Europe today.

The Great Stagnation

Europe is still a manufacturing powerhouse, responsible for about one-third of the world’s exports. But when it comes to value creation, they are losing the game.

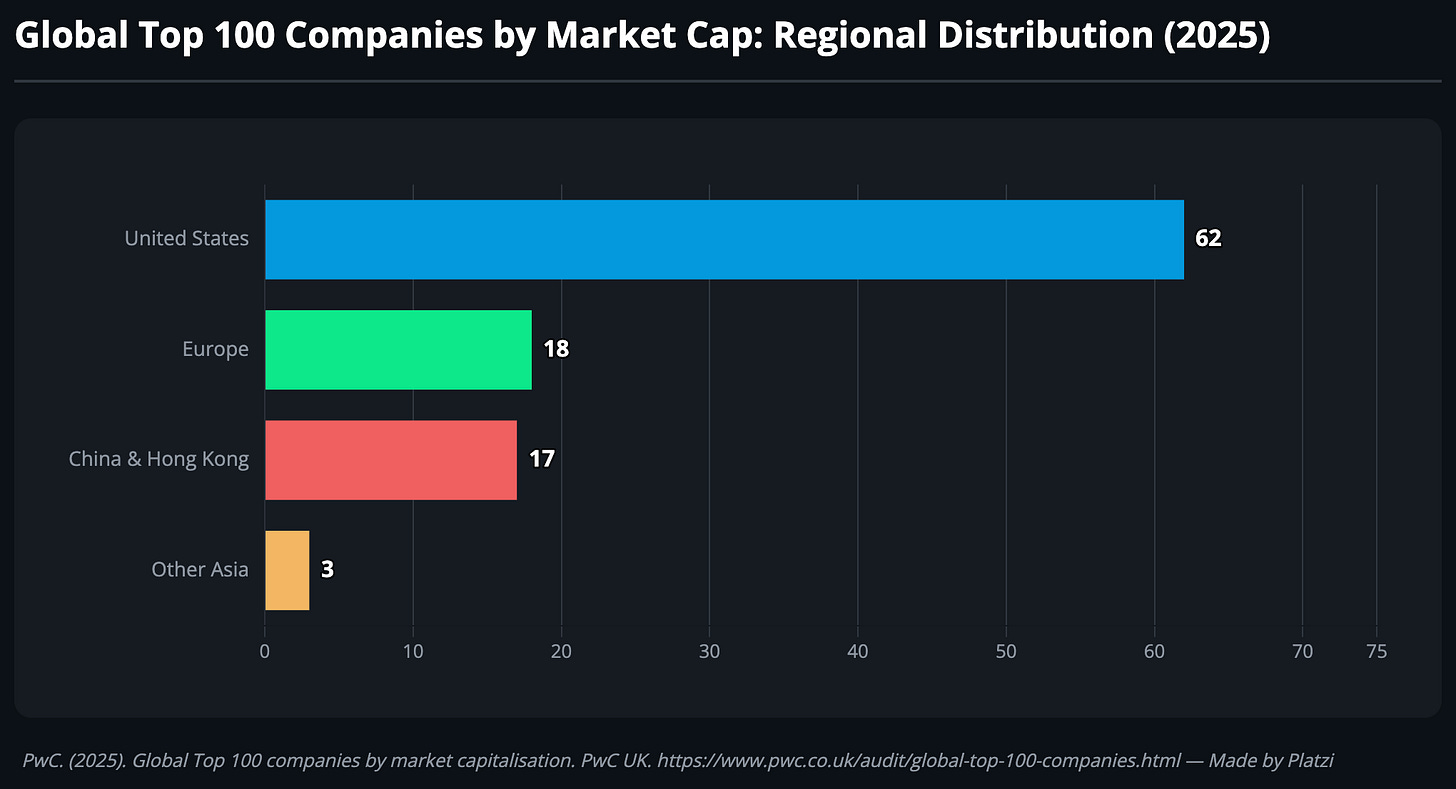

Look at the top 100 most valuable companies in the world. The US has 62. China has 17. Europe? Only 18.

And if you look at what those companies do, the problem gets worse. The US dominates in tech and innovation. The European list is luxury bags (LVMH, Hermes), legacy meds (Novo Nordisk, Roche), and oil (Shell, Total). There is only one true tech giant in Europe: ASML.

In startups, the US has 700+ companies worth over $1 billion. China has over 300. The EU barely cracks 100.

Why? Two main reasons: Investment and Energy.

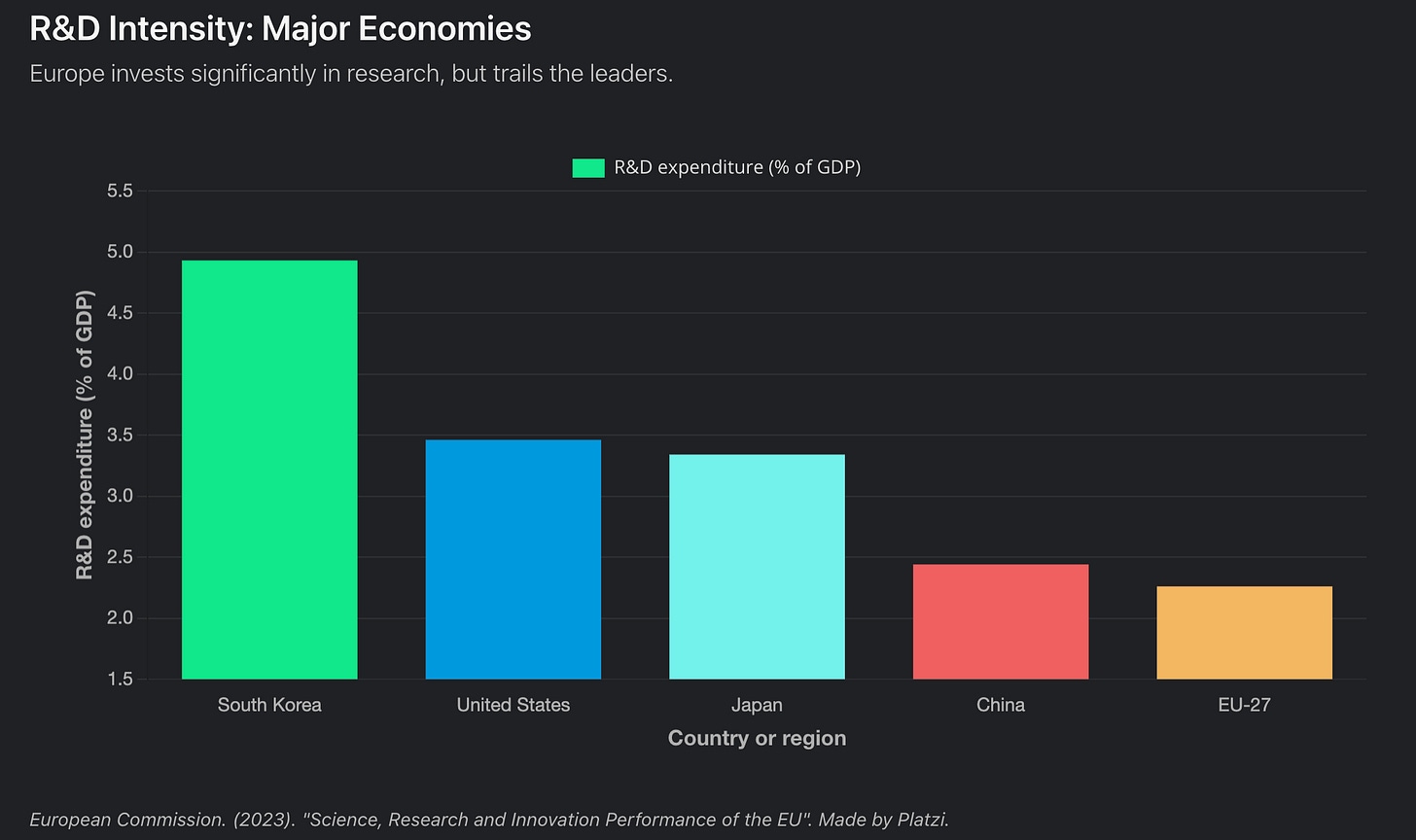

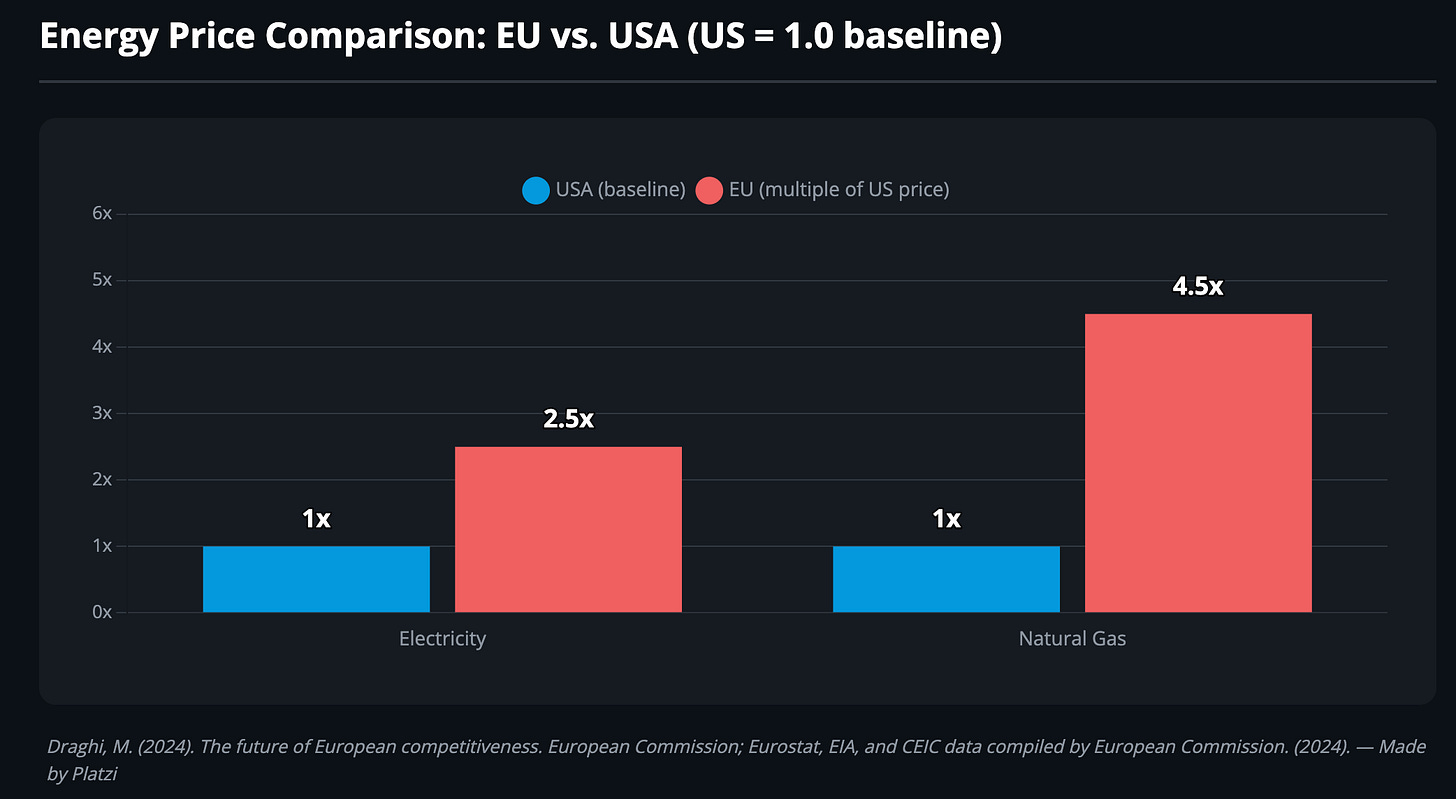

Europe doesn’t invest enough in R&D compared to the US or South Korea. But more importantly, they broke their own energy market. Electricity in Europe costs 2.5x what it costs in the US. Natural gas costs 4.5x.

This was a self-inflicted wound. Driven by disinformation campaigns (often fueled by Russian interests) and the panic after Fukushima, countries like Germany shut down their nuclear plants. They traded energy independence for a reliance on Russian gas and expensive imports.

The Microwave Salesman Who Bought a Robot Empire

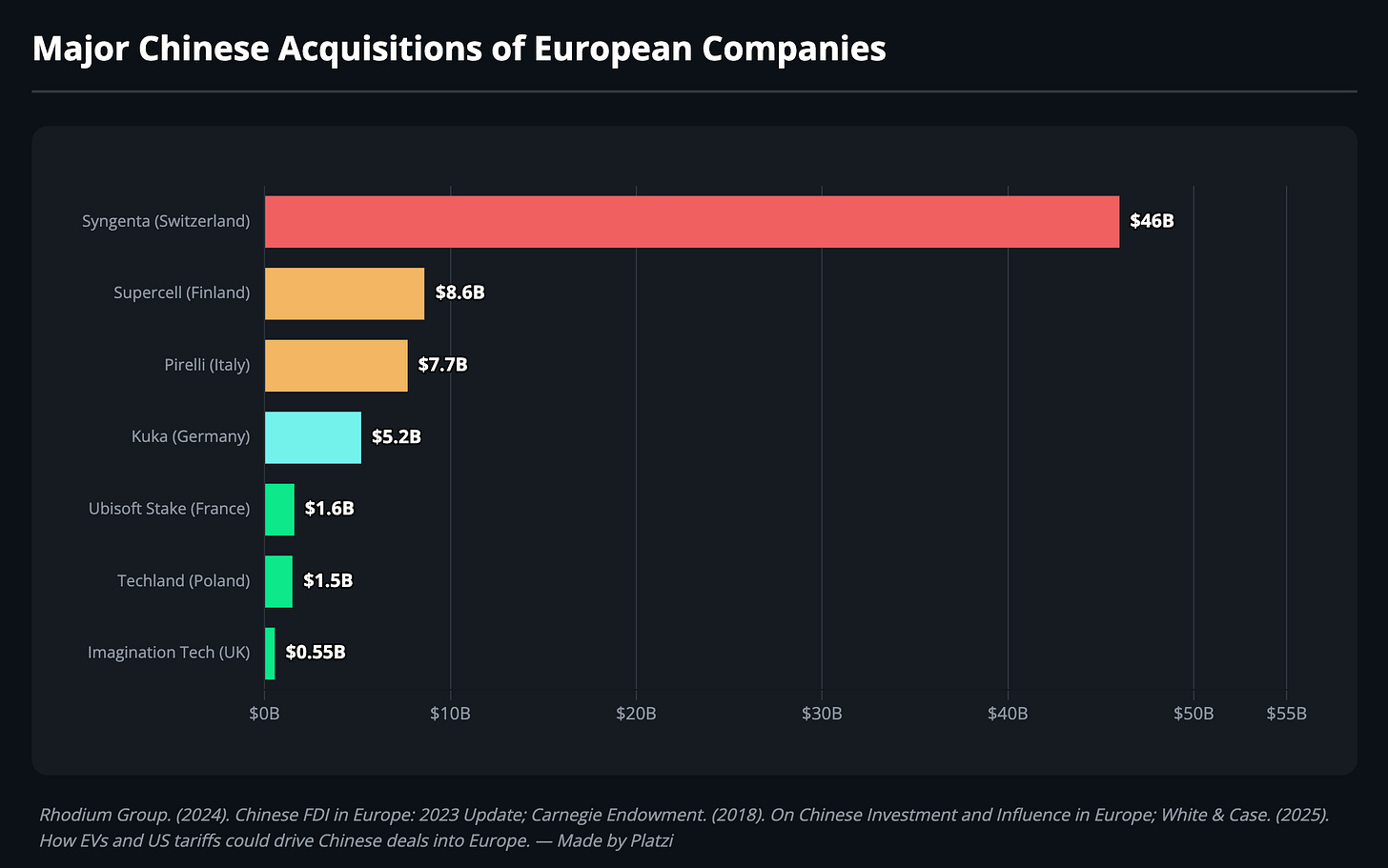

While Europe was sleeping on energy, China was buying their companies and using that acquired knowledge to build their own.

China spent years acquiring European manufacturing capability. They bought Syngenta (Swiss agri-tech), Pirelli (Italian tires), and Volvo. But the most embarrassing loss for Europe was KUKA.

KUKA was the crown jewel of German engineering. Along with the Swiss firm ABB and Japan’s FANUC, they controlled the global market for robotic arms. If you saw a robot building a car in a factory, it was likely a KUKA.

About ten years ago, the founder of a Chinese company called Midea approached KUKA. Midea makes microwaves, blenders, heaters, etc. He wanted to do business but the Germans, in their high castle of engineering superiority, ignored him.

So, the microwave salesman went home, raised billions and started secretly buying KUKA shares.

By the time Germany realized what was happening, Midea owned a controlling stake. The European business community panicked. They tried to get Siemens or ABB to save KUKA. Everyone said no.

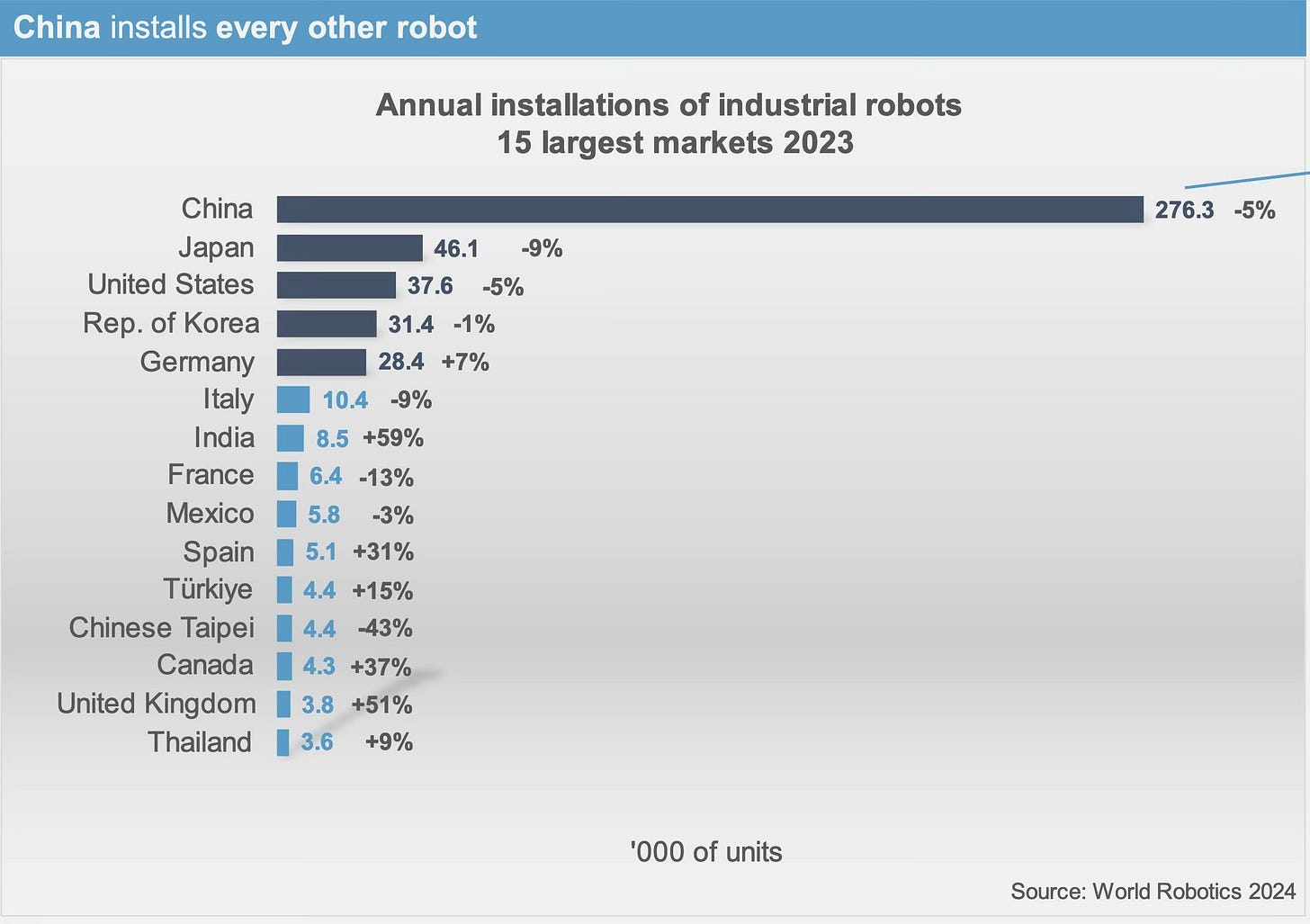

Today, KUKA is Chinese and China, which used to be a nobody in robotics, is now the largest market for industrial robots in the world.

The Demographic Cliff

Europe’s other massive problem is that it is running out of Europeans.

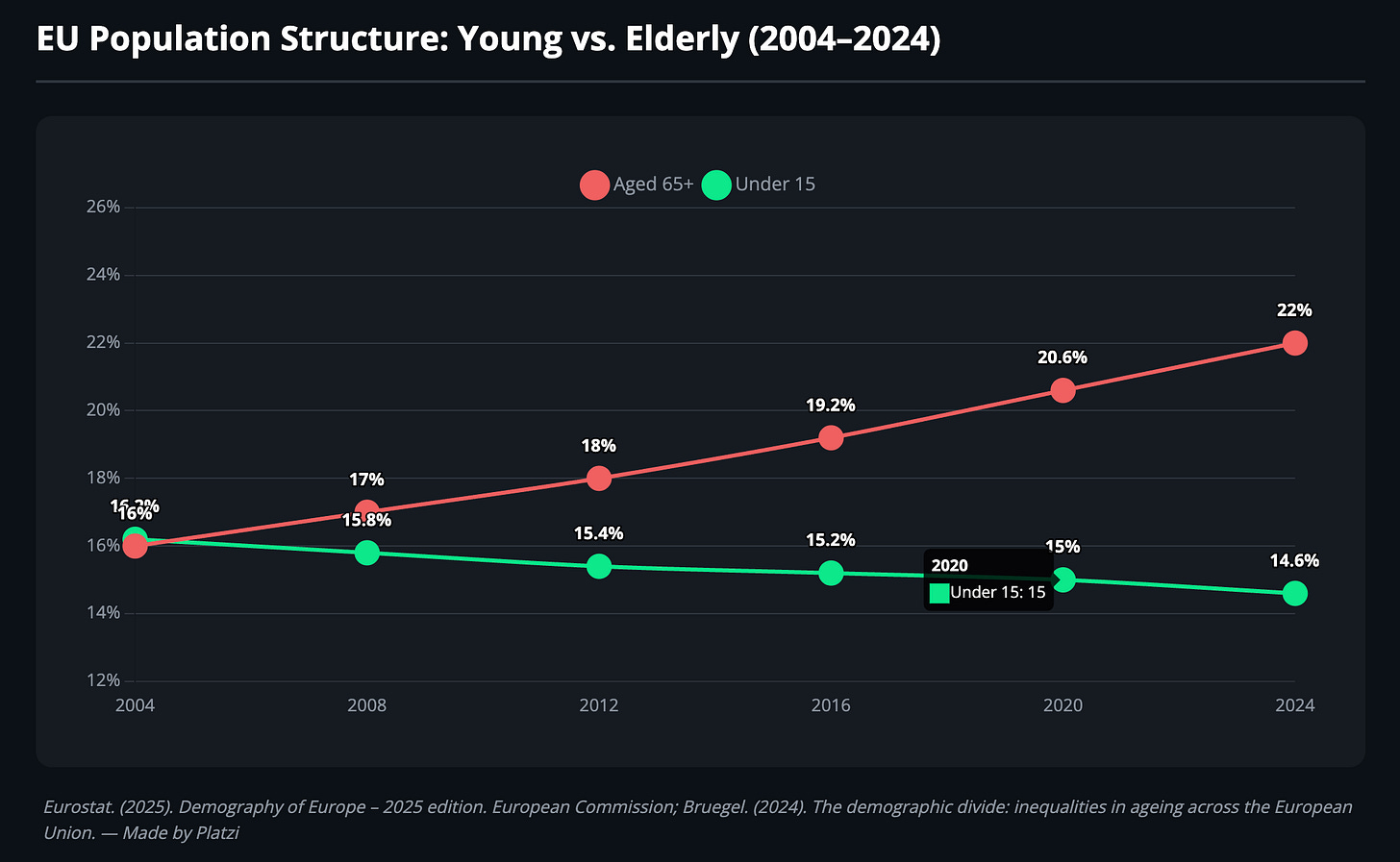

To replace a population, you need a fertility rate of 2.1 children per woman. Europe is at 1.4. The only country slightly bucking the trend is France, but that is driven almost entirely by migration, not by the locals suddenly feeling more romantic.

In 2004, the number of Europeans over 65 surpassed the number of those under 15. The gap has been widening ever since.

The continent is turning into a massive retirement home. Voters want pensions protected, but they don’t want the migration required to fund those pensions, nor do they want to raise the retirement age. It is a mathematical impossibility that hasn’t hit the breaking point yet. But it will.

The Hidden Monopolies

If you stopped reading here, you’d think Europe is finished. But remember ASML?

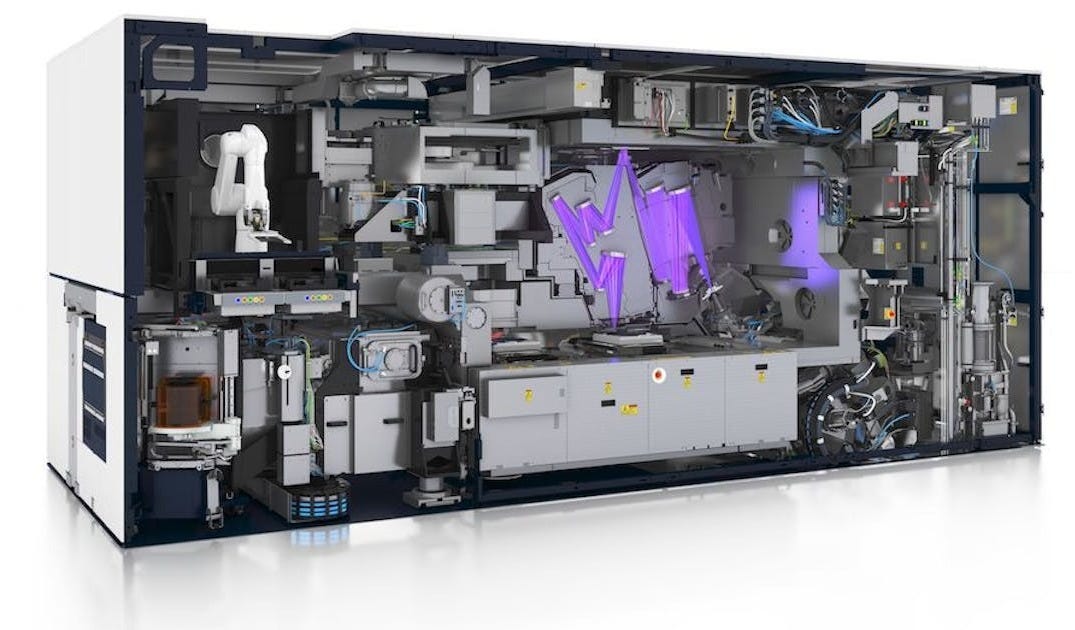

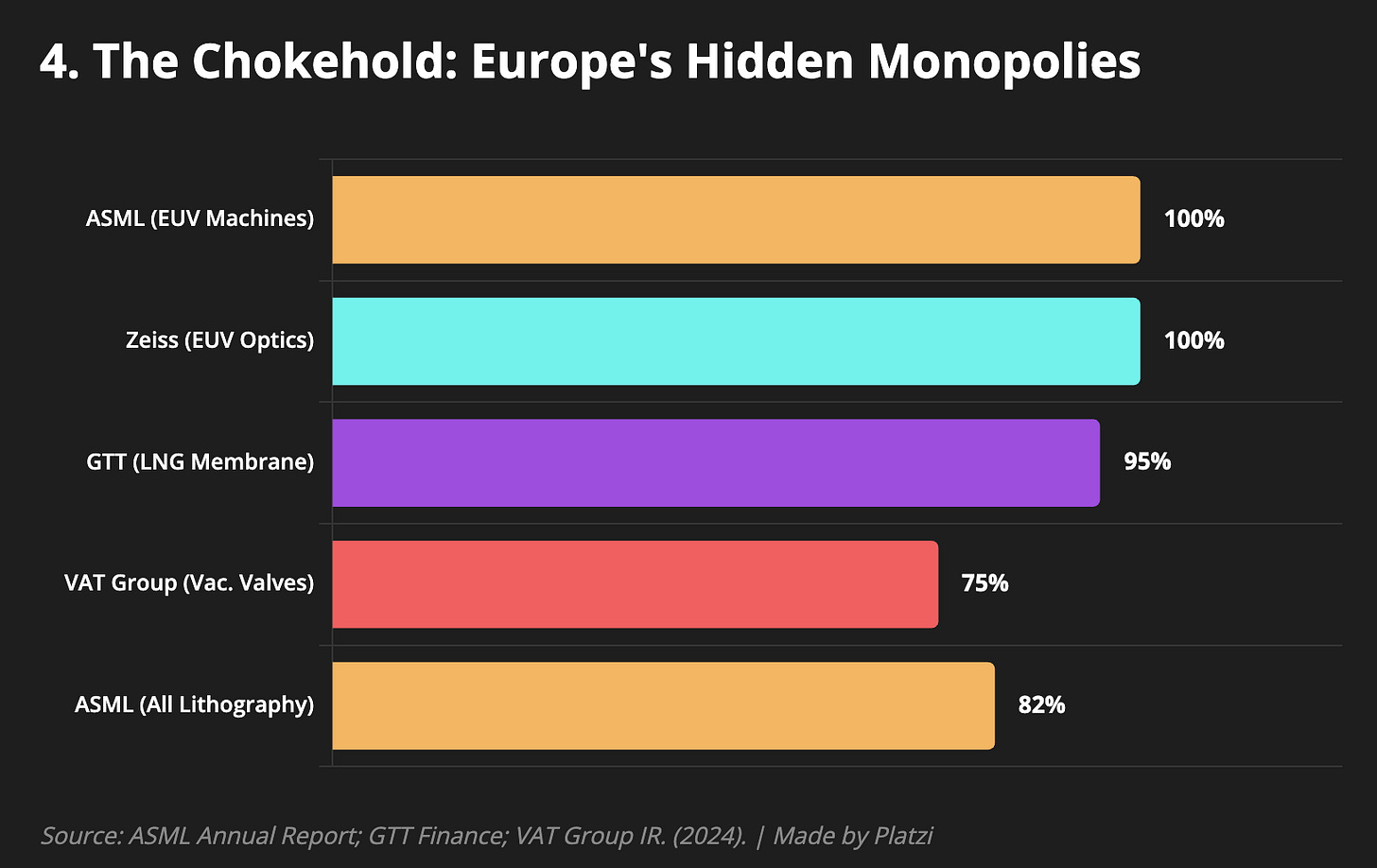

ASML is a Dutch company that builds Extreme Ultraviolet (EUV) lithography machines. These are the most complex machines humans have ever built. They are the only machines capable of making the advanced chips inside your iPhone, your NVIDIA GPU, and modern missiles.

No one else can make them. Not the US, not China, not Japan. The entire global digital economy rests on one company in the Netherlands.

But it goes deeper. Europe has mastered the art of the “Hidden Monopoly.”

Carl Zeiss (Germany): Makes the optical lenses ASML needs. No Zeiss, no chips.

GTT (France): Holds a 95% market share in the membranes needed to transport Liquid Natural Gas (LNG).

VAT Group (Switzerland): Controls 75% of the market for high-vacuum valves required for precision manufacturing.

China might be the factory of the world, but their factories run on European machines. Russia’s war machine? It depends on European industrial tooling to manufacture artillery.

Europe has no Google, no Facebook, no Amazon. But they are humanity’s “back end.” They control the physical infrastructure of high-tech manufacturing.

The Regulation Paradox

Finally, there is the European obsession with regulation.

Sometimes, this is great. The EU forced Apple to switch to USB-C, which was a win for humanity. The GDPR forced Google and Apple to connect Airdrop between Android and iOS.

But it can be self-destructive.

We have an internet broken by cookie banners because of EU laws. Apple Intelligence and many new AI features aren’t launching in Europe because of the AI Act. The regulation is so stifling that ambitious European founders incorporate in Delaware and move to San Francisco rather than stay.

Europe is a paradox: A region that regulated itself into stagnation, allowed its energy security to collapse, and sold its best robotics to microwave salesmen. Yet, it remains the silent engineer behind the world’s most critical technologies.

Is Europe dead? No. But it is certainly waking up to a very harsh hangover.

Freddy, loved the piece. Sharp, uncomfortable and needed.

But I hope you’re already working on the real question: is there any credible path for Europe to reverse this trend, or have they already crossed a point of no return?

I’m actually more pessimistic than your essay suggests, especially after digging into the structural data on demographics, energy, regulation, innovation and capital formation.

On a personal note: I’m one of the ~5,000 people who attended Platzi Conf México in May 2025. Great event.

I’m also subscribed to Platzi with four family members, including my daughters, and we’re all deep into the learning ecosystem you’ve built.

My youngest (just turned 18) lived one year in Germany, speaks fluent German, and is now deciding whether to study engineering or finance in Mexico (TEC or ITAM) or in Germany (TUM or TUB). I’m pushing her to run a rigorous pros-cons analysis: Germany’s promise of excellence vs. Mexico’s dynamism and growth tailwinds.

Curious to hear your take: would you still bet on Germany for the next decade?

Regards from CDMX

“Europe is becoming a museum run by compliance officers. You can regulate growth, or you can generate it. You cannot do both. They have chosen to be the world's referee while everyone else is playing the game”